Every disaster is also an opportunity for innovation. Unexpected problems sometimes beget unique solutions. The Covid pandemic caught humanity unprepared. The sheer scale and speed of the spread of Covid shocked us into reappraising our health care and information flow systems.

The usual expectation was that those at the bottom of the pyramid would be the most impacted, but Covid surprised us. Many called Covid the great equalizer because it touched and affected everyone irrespective of economic and social statuses. But over time it became apparent that the poor, marginalized and rural populations were markedly worse served both in terms of access to health services and vaccination, and access to correct information. Cheap internet, and popular messaging services like WhatsApp combined with videos and forwards of unverified and harmful misinformation exacerbated the problem. Vaccine hesitancy augmented the problems of weak infrastructure and the brunt was borne by the marginalized.

In this background, Google News Initiative funded The Quint-led collaborative project to tackle vaccine misinformation and empower the most underserved audience in rural India: the women. Video Volunteers Network (VV) partnered with The Quint for the implementation of the project in the Indian states of UP, MP and Bihar. Other partners in the project are Khabar Lahariya, Boat Clinics of Assam and Radio Brahmaputra. The project seeks to source hyper-local misinformation and distribute fact checks through a grassroots network of rural women.

Fake news and misinformation about the viral disease and its vaccine were spreading through the use of social media sites like YouTube, Facebook and WhatsApp. Many had believed such news to be true without verifying it and refused to get vaccinated. Something needed to be done to counter the misinformation with correct, verified news and that is how this project was conceptualised.

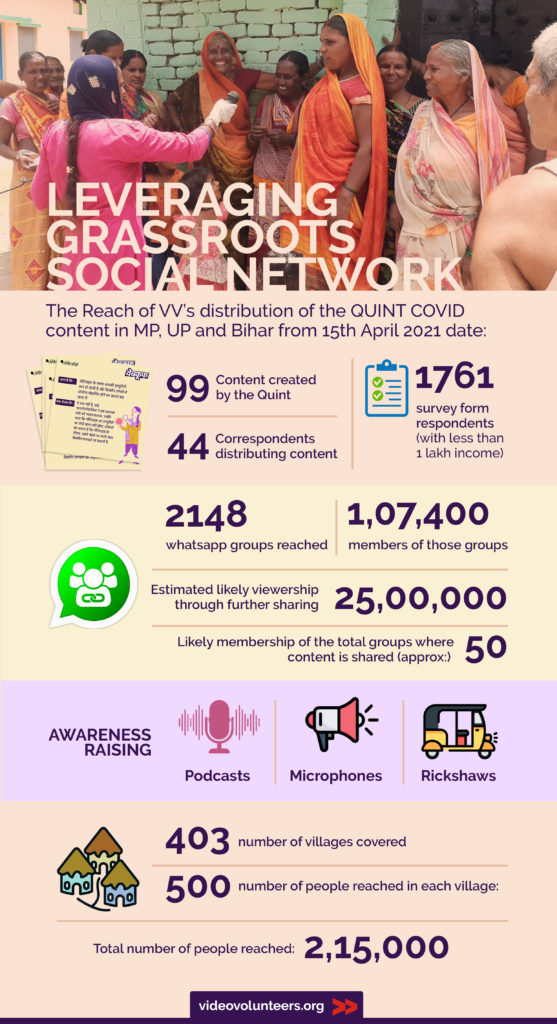

The broad approach of the project, which started on 15th April 2021 and will end on 14th April 2022 date, is for VV to use its network of Community Correspondents (CCs) across 40 districts of UP, MP and Bihar to source hyperlocal misinformation and share it with The Quint. VV conducted an initial survey of the underserved population to understand what perceptions people had about Covid vaccination and what their main sources of information were. After the initial survey, VV correspondents began to provide The Quint with hyperlocal misinformation using WhatsApp. The Quint would then fact check the information with the help of external experts and create audio, video, picture and text content that busts misinformation. This fact-checked misinformation debunking content in the form of posters, videos, podcasts and articles is currently being distributed at the grassroots by VV in UP, MP and Bihar. VV is also providing Quint with stories and audio-visual content to produce videos. The project aims to work closely with ASHA Workers, an all-women community health force instituted by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

VV has a network of more than 200 community correspondents (CCs) spread across 19 states of India covering 196 districts. The correspondents come from among the most marginalized communities of India and mostly from rural areas. A vast majority comes from a Dalit (Scheduled Caste) or Adivasi (Scheduled Tribe) community and more than 50% of the correspondents are women. The VV correspondents provide the service of a local journalist and activist at the grassroots. As a journalist they video document and share stories of issues affecting their communities and as an activist they mobilize the community and present this video evidence to concerned government functionaries to resolve the issues. The model is unique in many ways but most importantly in its use of technology. Each VV correspondent is equipped with a smartphone, internet and some filming related paraphernalia such as tripods and lapel mics. They are trained to film and edit on their phones, they can very quickly conduct surveys on their phones and they know how to use social media for micro-campaigning. They are strong in technology: they use the VV inhouse custom database to pitch stories, make advocacy plans and extract information; they can attend and conduct trainings using platforms such as zoom and they can do live telecasts. All of these skills were used in the GNI-Quint-VV project to tackle misinformation and vaccine hesitancy.

Phase-I

The first phase of the project was marked by the beginning of the second wave of Covid spread in India. This restricted the movement of the VV correspondents outside their homes and in their community. Fortunately, the VV correspondents were trained in using smartphones for reporting and advocacy and this came handy in meeting the goals of the project despite the constraints. We decided to use the correspondents’ local reach via their WhatsApp Action Groups to distribute the content created by The Quint with our help. Over the last few years, VV correspondents (CCs) have been trained in using WhatsApp as a medium of advocacy and mobilization. Each CC has created WhatsApp Action Groups to share their own content, showcase VV network content and advocate for the issues they cover. CCs are influential members of their communities so they are also members of various other WhatsApp groups of reporters, activists and civil society members.

We had three tasks to accomplish in the first phase- collect and share misinformation from the ground with Quint for them to create content for distribution; conduct a survey of at least 1000 people to understand what people at the grassroots thought about the pandemic and vaccination, what their sources of information were and how they viewed common misconceptions; and lastly distribute the content as widely as possible through social media and messaging services.

Each of these tasks came with its own set of challenges - from how to track the distribution of our content through multiple WhatsApp groups to conducting a survey without stepping out when a global pandemic was still lurking and very much active. We wanted accurate information while limiting our physical interactions.

Misinformation

We had committed to have 40 CCs working from 40 districts of UP, MP and Bihar, but we engaged 44 to ensure that the goals of the project were met. First, we organized a zoom call with all the CCs that we had in these three states to ascertain interest in the project. 44 CCs were selected to participate in the project keeping a few in buffer lest we fall short of any deliverables. We created a WhatsApp group for this project for CCs to share information on. The selected CCs were briefed about the project over Zoom and WhatsApp messaging and they were asked to start sharing any misinformation that they came across on the VV-Quint WhatsApp group. The CCs participated in this exercise with gusto, often sharing information that was not relevant e.g. general Covid related forwards or news. The VV project manager and Quint staff reminded CCs to only share forwards of misinformation that they came across but it took a few calls for the CCs to fully grasp what they were supposed to share.

The two main reasons for this were

-

The intelligibility of Zoom trainings depends on the participants’ equipment and internet connections- both not always perfectly functional for all the CC participants. The CCs might not have entirely comprehended what needed to be done.

-

CCs shared information that they needed verified. They shared whatever information they came across. To us from our position of privilege it seemed like just information and not ‘misinformation’. But for the CCs this was perhaps the first opportunity to verify the correctness of the oceans of information they were getting.

Later on towards the end of April 2021 (22nd April) the Quint microsite for uploading content got ready and then on the VV Project Manager would take the curated relevant content from the WhatsApp group and upload it on the microsite.

Common Misconceptions

Some of the most common misconceptions shared were:

-

Corona Vaccine will reduce the fertility of men.

-

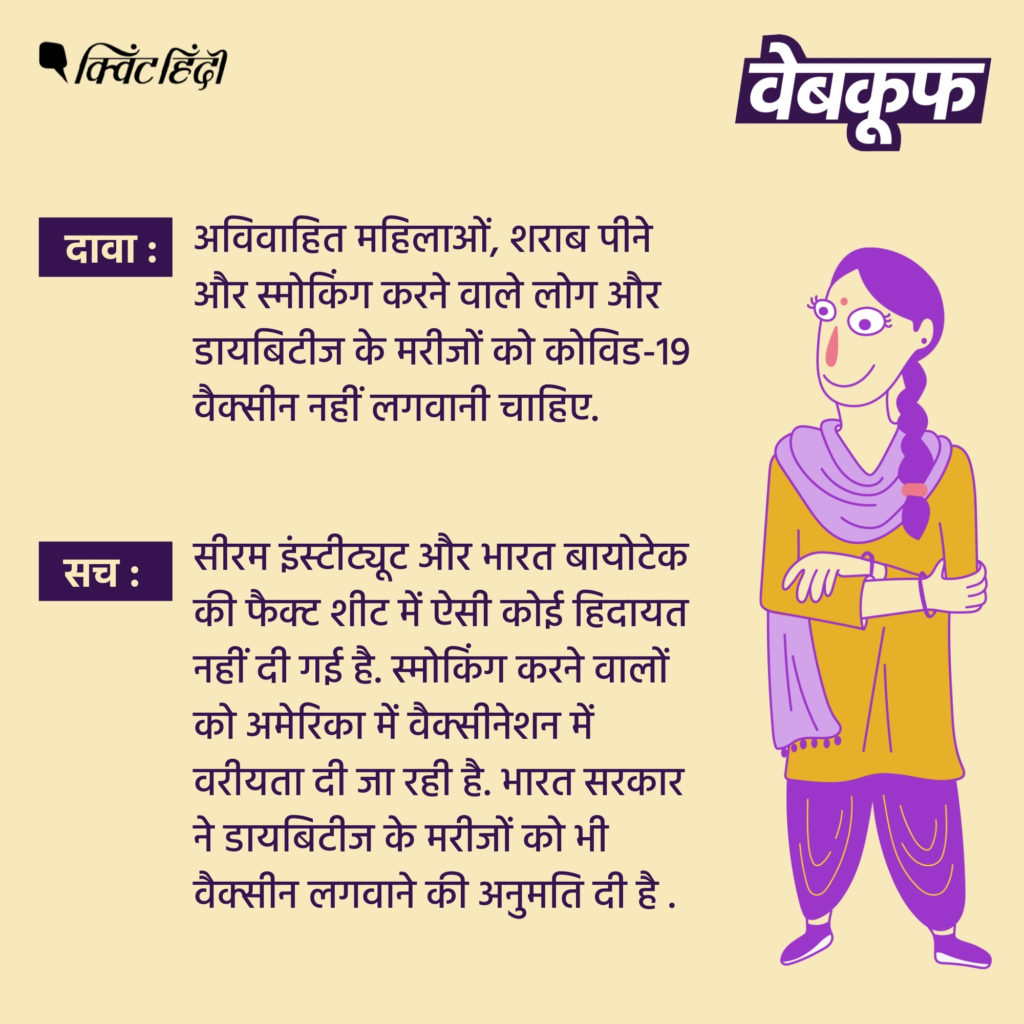

Unmarried girls, smokers and diabetic persons should not take Corona vaccine.

-

Corona vaccine will actually increase the virus infection in the body.

-

Corona vaccine causes death.

-

There is no Corona and Covid is nothing but a government propaganda.

Survey

The survey was rolled out to all the CCs participating in this project and it was conducted between 28th April and 12th May 2021 (two weeks).

The purpose of conducting this survey was to understand the perspective of the rural and urban poor communities about Covid and Covid Vaccination. We also wanted to find out what the main sources of information were for the poor for Covid and vaccine related information.

A list of survey questions was created by the Quint team and this was refined and translated by the VV team. The survey was longish with 37 questions, but the questions were simple with most being multiple choice or check boxes so we decided to use Google Forms as a platform for conducting this survey. The VV CCs are trained in conducting surveys on their smartphone using various surveying platforms, including Google Forms. The translated questions were uploaded on Google forms, the rules of survey were decided, which were - the survey would be conducted for two weeks; each form must be accompanied by either a selfie photo of the CC with the respondent or a photo of any government ID card of the respondents; no more than 5 responses from a village were allowed; generally speaking, no more than one response from a household was allowed, but if the respondents were of different genders then a CC was allowed to collect up to two responses/survey forms from a household etc., payment rates were decided and a Zoom meeting of the CCs was organized to roll out the survey.

We had committed that the survey would be conducted over at least 1000 participants. The actual number of participants were 2311. Because the focus of the project were the “underserved” population, we decided to consider only those respondents to draw our conclusions upon whose annual household income was less than Rs.1 lakh. There were 1761 survey forms, or about 76% of the respondents that participated in the survey exercise.

Each survey form was verified by the VV Project Manager to make sure that pictures were received. She tracked the survey results and followed up on individual CCs to get the verification pictures for each of the 2311 survey forms.

The survey results were analyzed and shared with Quint who published it as an article on their website. The survey confirmed that the poor were suspicious of the vaccine with 55% of the respondents expressing fear of the vaccine. One major conclusion of the survey was that even among the poor, the respondents from traditionally marginalized classes such as scheduled castes and scheduled tribes were found to be markedly worse informed than the others.

Distribution of Content

The most important aspect of VV’s role in the project is distribution of the content related to vaccine misinformation that Quint would create. Quint came up with easy to understand posters that debunked the common myths that the CCs had been sharing on the VV-Quint WhatsApp group. The posters centered on the character of Janki Didi who would bust common misinformation that are spread usually as WhatsApp forwards.

They also wrote short fact checking articles and created videos, again around the ‘Janki Didi’ character, for distribution. We shared the first video that The Quint had made with our CCs to get their feedback. The general feedback we received was positive and the CCs found the videos easy to understand and the character of Janki Didi relatable. We communicated this feedback to The Quint with some additional inputs.

The initial plan at the time of planning for this project was to have CCs do physical in-person distribution by doing screenings, putting up posters in PHCs and government offices and distributing pamphlets in their localities, but due to the second wave of Covid in India we changed tracks and redesigned our strategy to focus on online distribution of content. The change in the strategy presented many challenges - how to ensure that the content is shared widely, how to ensure that the content is not only shared but shared in such a manner that it gets traction and viewership, how to track at least the first level share of the content, how to encourage CCs to share each content etc. The CCs had started sharing misinformation on the VV-Quint WhatsApp group frequently and The Quint fact-checked the most common misconceptions very quickly and sent us their misconception-debunking content. Initially, we decided to bundle the posters, articles and videos together into projects and asked the CCs to share them in as many WhatsApp groups as they could and to also share them on their personal Facebook, Instagram and other social media handles. Rules were established and evolved as we moved forward in the project e.g. we decided that CCs will need to share the name of each group where they send the project along with the number of members in the group. Each group should have at least 20 members and while the CCs can do individual forwards of the projects, they will only be paid for forwards to a group or a share on their own social media. We also set an incentive for them if they were able to get one of the Quint videos to run on a local channel or if they could get one of the Quint articles to be published in a local newspaper. CCs were asked to share screenshots of each share, which we verified individually. After the first two projects, we realized that the cross checking of the photographs sent by CCs of their WhatsApp shares was inordinately time consuming, so from project-3 onwards we created google forms for the CCs to fill with group details -- names, number of members etc. and the VV Project Manager was asked to do spot checks of the photos sent by CCs instead of checking each photo.

The projects (posters, articles and videos) were shared widely over WhatsApp e.g. Project-2 was shared by 35 CCs in 2148 WhatsApp groups. Each group had 20 to 250 members. If we assume the average number of members in a group to be 50, we can estimate that at level-1 project-2 content was seen by 2148 x 50 = 107,400 people. The level-2 further sharing of the content by group members was not tracked by us but if we estimate that if 5% of the people (about 5000) further shared the messages in 10 groups each, the messages potentially reached 5000 x 10 x 50 = 25,00,000 people.

From project-3, three CCs got the article shared with them published in local papers and one CC got the video played at a local channel.

Stories for Quint

Some of their stories were also covered by the Quint.

The CCs working on the ground cover important and interesting stories that are often missed by the mainstream media. One of the requests that The Quint made at the beginning of the project was that we share with them inspiring and interesting stories from the ground. In May 2021, The Quint gave us a video brief of the kind of stories they wanted from the ground. They wanted three types of stories:

-

Major impacts of vaccine related misinformation e.g. a whole village refusing to vaccinate

-

How are people getting affected by misinformation and what is the impact?

-

The real damage of the Covid pandemic- are the government declared data correct or is the actual impact much worse?

We asked the CCs to pitch stories that they came across, two of which would be selected by The Quint for production. 13 stories were pitched by 11 CCs. Three of these were shortlisted by The Quint and their production is in the process. The three stories are:

-

Sita Devi from Bihar - A story from Araria, Bihar about vaccine misinformation. The pitch speaks about people saying that they have pledged to not get vaccinated because they know that the reaction of the vaccine causes fever, fatigue, illness, and as a result, they will die just after being vaccinated. They believe that humans are going to die one day so why not from COVID-19. They pledged not to go for a COVID checkup and they will never take the vaccine. This story was published by the Quint here:

2. Sita Devi from Bihar - Another one from Araria, Sita Devi talks to the hospital manager about work distributed and facility provided to ASHA workers and NM in this pandemic, the manager replied that ASHA is responsible for the village survey and identifying people who get fever and cough. He replied that he has less amount of thermometer and oximeter to check up on villagers, so he provides them to some ASHA workers only. When Sita Devi talks to ASHA workers they totally deny getting any information about the survey or protective gear because there is no meeting or anything conducted in their presence.

3. The third story is by Kesha from Uttar Pradesh in which villagers are talking about how they have no information on COVID-19 vaccines. There is no one around who talks about the importance of the covid vaccine because there is no ASHA worker or ANM around to be aware of the vaccine. They only wear a mask and wash their hands to protect themselves from corona and have no other information regarding corona. They were willing to know about the corona vaccine and were still waiting for any ASHA worker or Government worker to inform them about the corona vaccine.

Challenges and Innovation

The uniqueness of this project meant that the design process had to start from scratch. In many ways we were equipped to handle this project, but it was also something that was quite different from our base model of community journalism that uses the method of shoot-share-solve to empower the most unheard voices of the country. One of the challenges for us was how to train the VV correspondents (CCs) on the different aspects of the project as it evolved over time. When the first wave of Covid had hit us, we had to quickly train our CCs to use Zoom on their phones. This skill came in handy during this project and we organized the project-related orientations and trainings over Zoom. We also created project specific messaging in the form of images that we sent to CCs. These images included information like rules of distribution and survey, the processes to be followed and the aims of the project, written in Hindi in an easy to understand language. We did not want these messages to get lost in the very active VV-Quint WhatsApp group so we created a broadcast list and also another WhatsApp group where only admins could send messages. The latter was done so that CCs could easily access all important information at one place.

Another challenge that we faced early on was that the CCs very actively started sharing a lot of content on the VV-Quint group, not all of which was relevant. To tackle this we conducted multiple Zoom orientation of the CCs to explain that only content that pertained to Covid related misinformation needed to be shared.

Doing the survey had its own challenges. Our CCs are well versed in conducting surveys using their smartphones. However, in the past all the surveys they did were done physically i.e. by physically finding respondents and having them respond to a questionnaire. Covid restricted CCs’ movement and we would not allow them to share the survey forms with respondents over messages. We asked the CCs to conduct the surveys over phone calls. The CC would use one phone to call a potential respondent, take their consent and then ask the survey questions while simultaneously filling the survey form on another phone. For verification we asked the CC to get a picture of any government id card from the respondents. We received 2311 verified responses i.e. we checked the government id cards and found them matching in 2311 response forms. This was a time consuming and tedious process but necessary to ensure the authenticity of the survey.

Once the content created by The Quint started to arrive, we met to discuss the strategy of sharing it. The original plan at the time of conceptualizing the project was that the CCs would distribute the content physically by organizing screenings and distributing posters and pamphlets. This was not possible at the time the project started due to the second wave of Covid and the ensuing lockdown. Our CCs knew how to use WhatsApp as a messaging tool and many of them often used it to share their videos with individual government functionaries and leaders to resolve the issues they are working on. But the CCs had never used WhatsApp to distribute content or to run an awareness generation campaign. We wanted the content to be shared in as many groups as possible and this meant that not only did the CCs have to share it in their existing WhatsApp groups, they had to try to join as many new groups as possible. To incentivize the CCs, we came up with a payment scheme that paid them for sharing the projectized content into a WhatsApp group. CCs had to take a screenshot of the content in such a way that the group name was visible and had to write down the number of members in each group. VV's Project Manager joined some of the groups for additional verification. We created Google forms for each projectized content that the CCs filled. This allowed us to get some numbers easily such as the number of groups the content was shared into and the number of CCs that shared content. We could not get the accurate number of members of these groups because while we asked CCs to name their groups with the number of members, this was entered in a text field and not in a summable individual field that would be too cumbersome and time consuming for the CCs to fill.

Towards the end of phase-I we realized that projectizing (bundling) the content, though convenient, was taking away from the shareability of the content. When a CC sent 4 pieces of content - such as a video, a podcast and two posters - it did not have the same impact as a single poster or video being shared in a group. When we realized this we changed tracks and stopped projectizing content in phase-II. We made rules of sharing that encouraged CCs to share one content in a day and to write a personal message to encourage group members to engage with the content and share it further.

Phase-II

The effects of the second wave of Covid started to cool down towards July. CCs reported that they felt comfortable going out and also expressed willingness to engage in physical distribution of the fact-checked information. Over the last few months many of the CCs had been involved in Covid-related relief work. In the second wave of Covid, we at VV had decided to actively engage in direct relief work in the CCs’ communities. We raised funds and offered CCs the opportunity to supply food packets, medicines and protective gear in their communities.

We even funded the setting up of a Covid care centre at Walhe in Pune district. CCs took a lot of initiative and more than 30,000 individuals were helped directly as a result of this work. In addition, we ran an awareness campaign in the tea garden areas of West Bengal that is estimated to have reached more than 300,000 people. Around 30 of our CCs suffered from Covid. Our CCs could see first hand the impact of the pandemic and the importance of getting vaccinated. In phase-II of the project we decided to begin physical distribution of the content. There was much misinformation doing the rounds in various forms and CCs were encouraged to share the new ones that they came across on the VV-Quint WhatsApp group for The Quint to factcheck and create content on. This process would continue as is but we decided to change the model of distribution of the content. In the second phase, the online sharing would continue albeit in a more refined and effective fashion but we would also begin to distribute the content physically on the ground. Many of the poor do not use social media or Internet-based messaging services. Daily wage workers and other economically marginalized rural communities that are denied vaccines or are afraid of getting vaccinated needed to be reached and offline physical distribution was the only way ahead.

Distribution of Content

In the first phase we wanted our CCs to learn to share content effectively online through social media and messaging services like WhatsApp. We accomplished this goal effectively and were able to reach a large number of people. We brought about the following major changes in our online distribution strategy

-

The first major change we brought about was that the content was no longer bundled into projects and each content had to be shared individually. CCs were also told to share one content in a day. We also started to send to them just one piece of content in a day to encourage this practice. We also changed our tracking form and instead of an individual form for each project, we made a common form. Each piece of content was given an easy to recall name such as ‘Kya hai Covid (article)’, ‘5G (video)’, ‘Alcohol (audio)’. The tracking form would have a drop down of the content names and CCs would need to fill one form for each content that they shared. Each individual content would only be available to share for a limited number of days after which it would be removed from the tracking form.

-

Another change that we incorporated was that the video content was not to be uploaded on WhatsApp but would be shared as a YouTube link. On Facebook though we encouraged CCs to do native uploads because our metrics tell us that native uploads get better views on social media.

-

Earlier we paid CCs for every share. This was done to encourage them to join as many groups as they could and to train them in sharing content. In this phase we stopped paying the CCs for just sharing and paid them for ‘effective engagement’ instead. This means that just sharing a poster in a group would not entitle a CC to some payment but they would need to show some kind of interaction or effective engagement with the group members. The content was not bunched into projects any more and CCs had to share individual posters, videos, articles and podcasts. Effective engagement would mean that the CCs would need to share the content in such a way that it generated interest. They would need to write an introduction - ‘Many people believe that the Covid vaccine is made of the blood of a newborn calf. Our team fact-checks this rumour’ or a catchy phrase - ‘new information about the delta variant’ or an intriguing question- ‘kya aap ko pata hai double mask kyun hai zaroori?’ One standard script was also shared with them that they could use to introduce a content.

The CCs had to show proof that some members of the group showed interest in the content in some way for it to be eligible for payments.

-

Another important change we made in our online sharing strategy was that we started to incentivise CCs to join new groups. At the last count, CCs had joined 65 new WhatsApp groups.

In addition to refining the online distribution strategy, we also started physical distribution of content. This was done in the following ways:

We assessed the type of content we had from The Quint- we had posters, articles, videos and podcasts. The podcasts were mostly the audio of the Janki Didi videos that they had made.

We considered what would be the most effective way to reach the maximum number of people in a short amount of time. Given the overall time span of the project, the original planning gave us about a year to physically distribute the content. If the second wave had not struck we could afford to do a sustained distribution over a year using individual screenings, group screenings and poster pasting in PHCs and hospitals. But since a lot of the time had passed, we wanted to create an event that would have us quickly reach a large number of people.

Narrow Broadcasting and Pamphlet Distribution

We decided to run a cycle of physical narrowcasting of audio content and pamphlet distribution. Our CCs would hire a cycle rickshaw or an auto rickshaw, loudspeakers and other broadcasting equipment and spend two days broadcasting Covid-related verified facts in their community. The rules we established for this exercise were:

Each CC would need to do two days of narrow broadcasting using a vehicle and audio equipment and distribute at least 100 and up to 1000 pamphlets.

CCs would share the plan of their narrow broadcasting exercise with the VV Project Manager over WhatsApp and take approval.

If the plan was approved, they would be given an advance to print pamphlets and to hire a vehicle and equipment.

The CCs had to cover at least 10 villages in the two days of narrow broadcasting. Or if they were doing their narrow-broadcasting in a semi-urban or urban area then they had to cover at least 10 muhallas. They were encouraged to stop near public service areas such as schools, hospitals, PHCs, Covid vaccination centres, government offices etc.

The podcasts made by The Quint were combined to create an almost hour long audio clip. Eight of the posters made by The Quint were combined to create two posters that would be used to print a pamphlet on both sides of the paper, each side with four misinformation debunking images. Both these were shared with the CCs who had to get the pamphlets printed locally.

For verification purposes, the CCs were asked to do either a video call with the VV Project Manager while they were doing the offline distribution or do a Facebook Live.

The CCs were also asked to make a video of the process and the rest of the payment would be made upon the receipt of the video made by them. In their video, they had to show their work and also interview some of the audiences. We organized a Zoom meeting in mid July 2021 to orient the CCs on this activity. They were instructed to ask questions, especially to women audiences, and record the response. They had to ask questions such as:

-

Do you understand the message being broadcast?

-

What do you think about Corona?

-

Have you taken the vaccines? If not then what is the reason?

-

How many people in your village are vaccinated? How many people are aware of vaccines?

-

What are people saying about Corona and vaccines in your village?

-

Is there any misinformation or rumor about Corona in your village?

-

What facilities related to Covid and vaccination are available in your primary health center? What other health facilities does your PHC offer?

-

What do you think about our initiative to create awareness about Covid?

The Quint also wanted interesting footage from this activity and we organized a meeting between CCs and The Quint managers in end July. They requested the CCs to do a vox-pop on the ground- gather some women and capture their thoughts, they asked CCs to collect bites of relevant new misconceptions that people share and to visit PHCs to assess the response to vaccination and see what facilities they had. They also wanted CCs to capture the response of the people on the narrow broadcasting activity. 43 of the 44 VV CCs engaged in this project captured vox-pop responses from women and other audiences.

43 of the 44 VV CCs engaged in this project captured vox-pop responses from women and other audiences

All the CCs engaged in the project had requested for advances and almost all had completed their two day loudspeaker broadcasting activity by the time of writing this report. Some CCs had given the feedback that printing 100 pamphlets was too few and we allowed the CCs to print up to 1000 pamphlets. Our conservative estimate is that each CC was able to reach 5000 people i.e. a total of 43 x 5000 = 215,000 people are expected to have been reached during this activity.

The offline distribution activity also received considerable local press coverage and many CCs shared newspaper clippings of print editions of newspapers of their areas. The offline distribution activity also received considerable local press coverage and many CCs shared newspaper clippings of print editions of newspapers of their areas.

Challenges and Innovation

While the challenges of the first phase of the project can be defined as teething troubles, the second phase brought more nuanced challenges. Online sharing was easy in the first phase because CCs were paid for simple sharing. In the second phase we coupled payments to ‘effective sharing’. This meant that the CCs had to not just forward a piece of content into a group but also engage the group members in a positive and constructive way. They were encouraged to continue sharing in the same number of groups, but we reckon that the online sharing in WhatsApp groups will have gone down in phase-II.

The offline distribution presented the challenge of verification. We saw this as an opportunity to train the CCs in using tools of social media and encouraged them to do Facebook Lives of their narrow broadcasting. One of our goals under this project is to have CCs emerge as leaders and social media influencers in their communities and we feel that the social media reach and presence of the CCs involved in this project have increased substantially.

Fighting for Change: The Story of Bihar-Based Journalist Amir Abbas

Inspiration can come from many sources, but one of the most powerful is seeing someone walk the path before you. Our Community Correspondent, Syed Amir Abbas found his inspiration in Stalin K., the founding director of Video Volunteers. “I met Stalin at VV’s national meet in 2017 and I...

The torch bearer of rights for marginalized tribals of Odisha

If you ask Video Volunteers’ Community Correspondent Bideshini Patel to rate her childhood on a scale of 1-10, she would probably give it a negative marking due to the neglect and abuse she faced. But if you ask her to evaluate her professional life as an impactful journalist, resolving basic...